The Rise of Newsprint

Newsprint is the headline here, born in Canada in the 1840s. Made from wood pulp, newsprint paper is cheap, strong enough to withstand industrial processes, and robust enough to handle four color inks without tearing -- provided control over the amount of ink is maintained.

Newsprint is named literally for its primary use, in newspapers. Off-white to begin with, newsprint is non-archival, meaning that it will yellow with age and exposure to sunlight, and will eventually disintegrate.

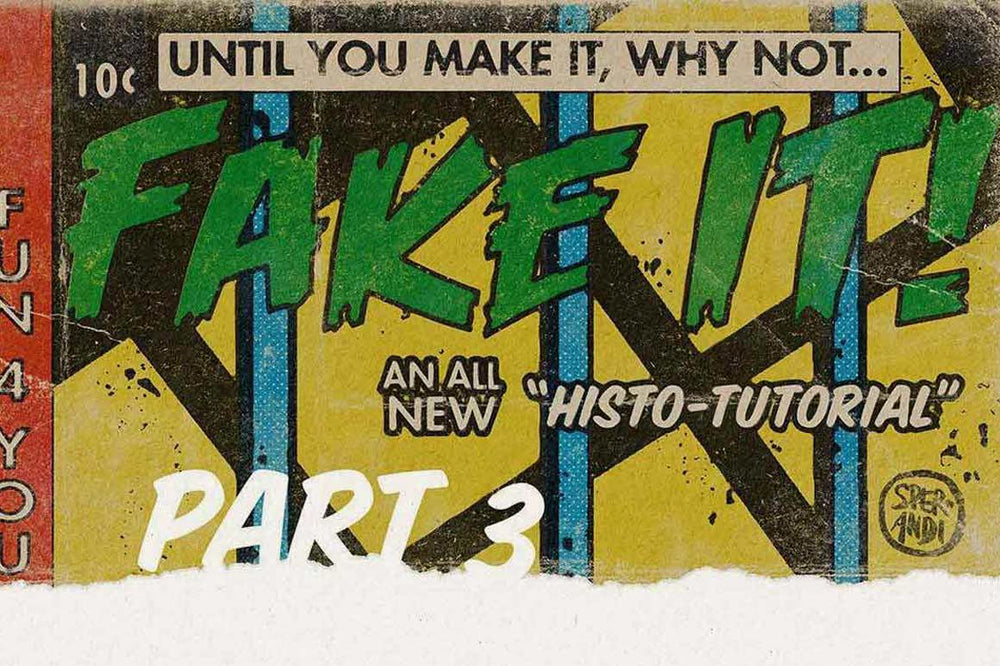

Take an old comic book (from the 1970s or earlier) and place it next to a sheet of computer paper from your home printer. The old comic will have an uneven yellow cast and the paper itself will be brittle. Depending on its condition, the old comic could even be moldy.

Again, the collector’s tragedy is our joy – meaning that the flaws and damage are the additions that will help sell our fakery.